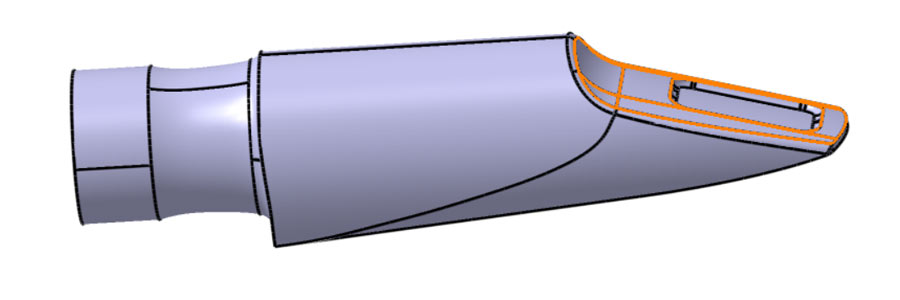

The most important of the mechanical features is the

facing curve. It delimits the travel of the reed, so both the tip opening (the distance from the tip to the plane of the table) and the length and precise shape of the curve heavily influence both the response of the mouthpiece and the sound. Longer facings tend to be less resistant (i.e., more free-blowing, less 'back pressure'), make the bottom end of the horn play more easily, as well as make subtone easier. Shorter facings tend to make response more well-defined and favor the top end of the horn and altissimo. That said, at any given length of facing and tip opening there are an infinite variety of possible curves, and deviation from a simple circular section (often referred to as a radial curve) is common practice to effect a certain resistance or response. The curves I use are medium in length, and are closely related to the traditional curves from the best of the 1950's and 1960's mouthpieces. There is a school of thought that making a long, radial, maximally free-blowing curve is optimal. I prefer a medium curve with a little bit of resistance built in. Having a little something to balance against when you're blowing gives you more control over the sound. Also playing a slightly softer reed or slightly smaller tip opening for the same feel of resistance gives you a more overtone-rich sound. That said, a minority of players have a strong preference for long (e.g. Michael Brecker) or short (e.g. Eric Alexander) facings, but by and large most modern reeds suit a medium facing well.

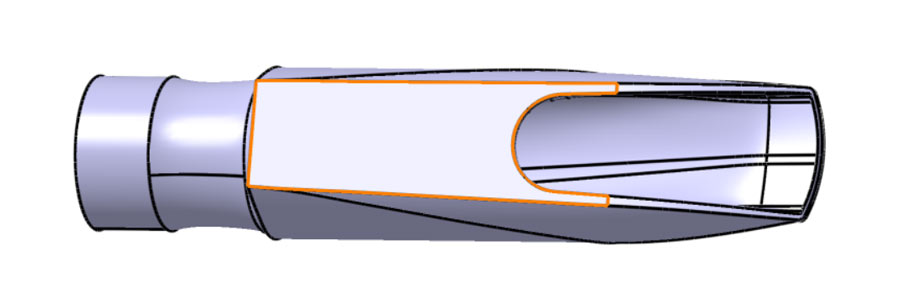

The

table is what the flat of the reed sits against. There are three shapes that are commonly seen -- flat, concave (dished), and convex (bowed). Many mouthpieces are made intentionally with either flat or concave tables. The concavity (sometimes called a "French curve") gives the reed some room to swell with moisture and still seal. It also might act as a bit of a springboard, making the facing curve play a little longer and more open than it measures. To what extent these are good behaviors is a matter of opinion. Also, when a concavity extends over the window it can cause air to leak if the reed isn't forced down enough by the ligature. Flat tables are also popular with manufacturers and refacers. It offers marginally less compliance room for a swollen reed, but in my experience a reed bad enough to push off the table needs to be scraped flat or replaced anyway for best response on any mouthpiece. Also with a flat table, the placement of the ligature makes less difference to the sound and response of the mouthpiece. Occasionally you may come across a convex table. This is always a mistake. You can force a reed down to conform to the table but it will never play for long. If you ever had a piece that reeds would just die after 20 minutes on, or in between sets, this is often the problem.

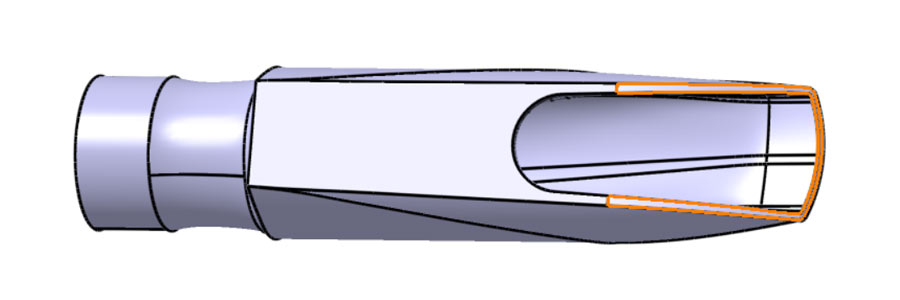

The

tip rail and the

side rails are what the reed beats against. Any material here dampens the vibration of the reed. This means that the thinner the rails, the faster the response is and (to a lesser extent with the side rails) the more edge is in the sound.Wide side and tip rails can be a useful feature for a beginner's mouthpiece, preventing some squeaking that can be discouraging in the early stages of learning. For a professional's tools, however, these can vary according to the sound and response you're looking for. A player who likes very little edge in the sound will tend to prefer pieces with a wider tip rail, whereas a player who wants more edge and more speed will prefer a thinner tip rail. It has been said that too thin a tip rail can cause a mouthpiece to be prone to squeaking. This is because a wider tip rail can cover up errors or idiosyncracies in the facing and baffle that cause a piece to want to squeak or chirp. But if there are no imbalances in these areas, the tip rail can be as thin as you want with no negative effects on response.

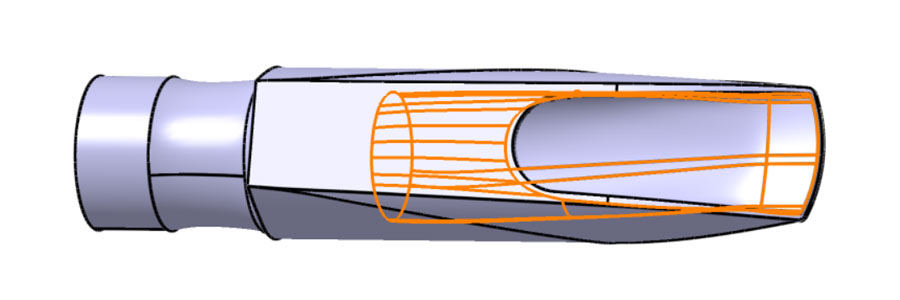

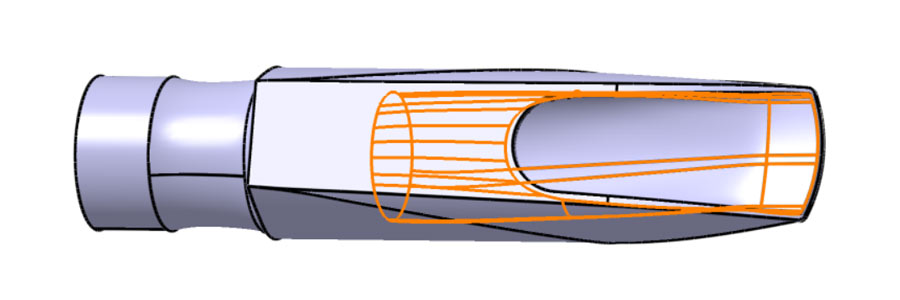

The baffle might be the hardest and most important feature to get exactly right. It controls entirely the aerodynamics of the mouthpiece. Long story short, forcing air through a smaller space (like from the inside of your mouth to the space between reed and baffle) speeds up that air and lowers the pressure of that air (the Bernoulli effect). The baffle of the mouthpiece is the area that does that. It ends wherever it is open enough for the air to slow down enough that the speed doesn't matter anymore (in the pictured model, that's about 7mm from the tip). The angle (or height) and length of the baffle are crucial. A more efficient baffle will cause the reed to close with less pressure from your end, causing the sound to be more edgy. So higher baffle -> more edge. But as it gets longer, it can start to also seriously impact the acoustics of the mouthpiece, making the chamber play as if it were smaller than it is. In extreme cases, this can also cause issues for the instrument's intonation.

There are a 2 main shapes of baffle -- straight, and rollover. A rollover baffle is one where the angle is constantly changing, highest toward the tip, sometimes even blending into the tip rail. This is seen more often in older (i.e. before 1970ish) mouthpieces than in more recent and current ones. A straight baffle is a constant angle w/r/t the table, and at the end can be either smoothly blended into the chamber or have a sharp drop into the chamber. I much prefer the response of a straight baffle which is blended into the chamber. I vary the height and length of the baffle according to the design goals for the individual mouthpiece. For instance, the Super Vintage has a higher and slightly longer baffle than the Vintage series but the same chamber. This different baffle is one of the design aspects that give it a more aggressive nature.

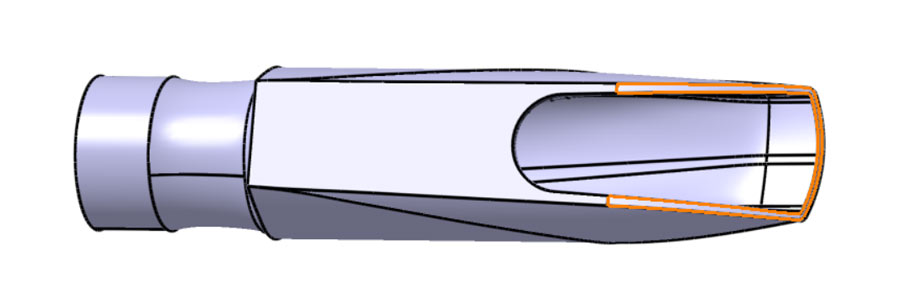

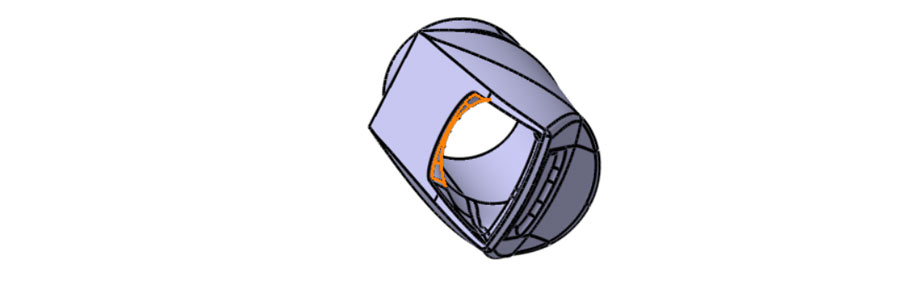

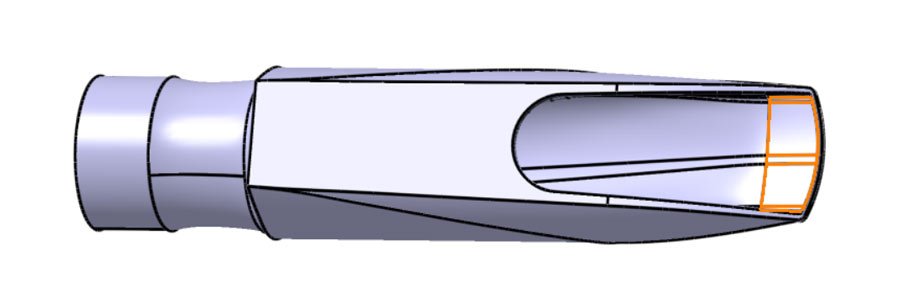

The

chamber is by far the most important feature. It entirely defines the acoustics of the mouthpiece. You can fine tune the way a mouthpiece responds and sounds by altering the facing curve and baffle, but you will always be constrained by the shape and size of the chamber. In general, a larger chamber will have a more spread sound than a smaller chamber, it will also be more flexible and so more dependent on the player to define the sound. The size isn't the only matter, though. The precise shape also matters significantly. It isn't just the sound that the chamber defines, it's the intonation. Assuming a given saxophone is designed and made properly, there exists an ideal mouthpiece chamber size for that combination of saxophone and player. At this size, the instrument will play very well in tune, and the higher overtones will be better defined (looking at the spectrum, you will see sharper peaks). This gives a richer, more colorful sound, as well as faster response and easier altissimo response. Still, for an accomplished player there is a wide range of theoretically sub-optimal combinations that work, and artistic concerns always trump theoretical ones. It is when you get very far from the acoustic requirements of the saxophone-player combination that a mouthpiece of the wrong chamber size can cause significant intonation problems. These usually manifest as things like palm keys being very sharp or very flat. Tip opening size also influences chamber size. From the point of view of the resonance column, part of the travel of the reed comprises the mouthpiece chamber. So a larger tip opening mouthpiece has a larger functional chamber than an otherwise identical smaller tip opening mouthpiece

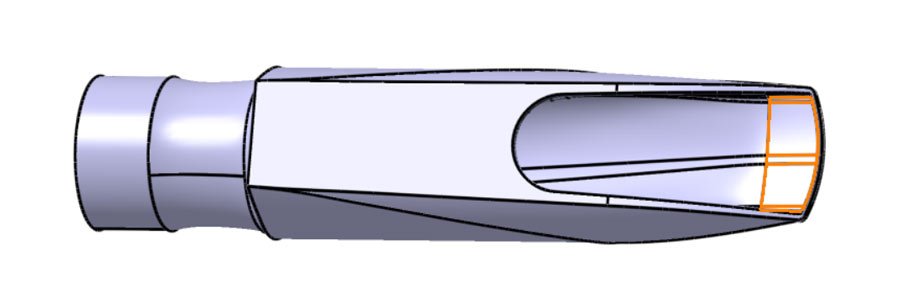

The

throat is the part of the chamber just past the window. Some alto mouthpieces in particular narrow here in a couple of different ways, often called a 'squeeze throat'. In some designs (e.g. Meyer Bros.) this gives a beautiful balance to the tone of the mouthpiece. In others it chokes off the sound and adds resistance. On most tenor pieces the throat is a simple continuation of the chamber, although there are a few that add rings and other shapes in this area to effect a particular sound.

The beak is the part you put in your mouth. The way it functions is more subtle than many of the other parts. The shape of the beak determines to some extent the shape of the oral cavity of the player, which strongly influences the sound. Some players like a tall, steep beak which makes the mouth open wide to play, some prefer (as I do) a narrower beak that puts the jaw in a more relaxed position, giving the player more flexibility to shape the sound.

In some situations, the acoustic resonance of the beak also becomes relevant. You ever notice how you can feel the mouthpiece vibrating via your teeth? If the beak is light and flexible enough, the pressure of the sound waves at the tip can move the beak enough that it influences the sound a little bit. My Original Ebonite mouthpieces exploit this property. With a very similar chamber to the Slant Vintage, by narrowing the beak I am able to achieve a little more centered sound with a little more edge.